Last week, the autopsy report came back and the pieces of the puzzle came together. It was proven that flesh-eating bacteria had killed the boy. The flesh-eating bacteria, also known as necrotizing fasciitis are potent enough to turn a wound as small as a pinprick into a massive infection, leading to amputation or even death, as in Devin’s case.

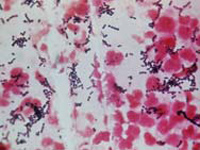

The infection is caused by bacteria, usually a type known as Group A Streptococcus (GAS), which thrive naturally on the throat and on the skin. The good news: Few people in contact with GAS will develop an infection, and it doesn’t appear to be very contagious. The bad news: No one yet knows why GAS sometimes becomes invasive.

GAS bacteria can enter the body through cuts and bruises. Sometimes, there might not even be an identifiable entry point. When the bacteria reach the blood, muscles or lungs, they can destroy muscles, fat and skin tissue. Hence it is termed as “flesh-eatingâ€.

If left untreated, the infected area begins to swell and appear bluish, white or flaky. Once it has progressed to this point, amputation of the infected area and immediate antibiotic treatment usually are necessary.

As scary as this may sound, most experts agree that there is little that can be done in the way of prevention. “Just cleaning wounds with soap and water is your best shot, but is probably of little use in general,†said Dr. Carl Schultz, professor of emergency medicine at the University of California Irvine.

Flesh-eating bacterial infections are more common in people with weakened immune systems, diabetics, or intravenous drug users — but healthy people also are vulnerable.