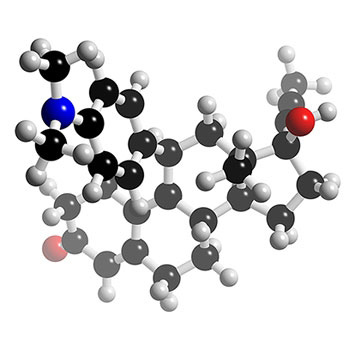

The chemical compound, called mifepristone, prevented breast tumors by reducing progesterone, a hormone involved with the female reproductive cycle, in breast tissue cells. The discovery points to new prevention methods for women who have a genetic predisposition to breast and ovarian cancers. At present, these women often have their breasts or ovaries surgically removed to reduce the risk of developing cancer.

Eva Lee, lead author of the study and professor of developmental and cell biology and biological chemistry at UCI said, “We found that progesterone plays a role in the development of breast cancer by encouraging the proliferation of mammary cells that carry a breast cancer gene.†Lee said, “Mifepristone can block that response. We’re excited about this discovery and hope it leads to new options for women with a high risk for developing breast cancer.â€

In the study, Lee and her colleagues tackled how mifepristone affects the function of mutated BRCA-1 genes in tissue. BRCA-1 is widely studied by cancer geneticists because a mutated version of this gene significantly raises the possibility of breast and ovarian cancers. By the age of 70, over 50 percent of women with the mutated BRCA-1 gene develop breast or ovarian cancer.

The researchers studied mice that carried the mutated BRCA-1 gene. Mice treated with mifepristone, an anti-progesterone compound, did not develop mammary tumors by the time they reached one year of age. All of the untreated mice, however, developed tumors by eight months of age.

Progesterone, secreted by the ovaries, is vital to the maintenance of a pregnancy. Mifepristone, also called RU486, is designed to abort pregnancy in the first trimester by blocking progesterone, thereby ending the viability of the fetus. In smaller doses, it is used as an emergency contraceptive.

UCI researchers found that progesterone encourages the development of cancer when the mutated BRCA-1 is present because it speeds up the division of cells. Mifepristone was found to block a binding process that is necessary for progesterone to cause the cell division.

Cancer specialists not involved with the experiment praised the work, even as they cautioned women not to get their hopes up yet.

“This is an avenue worth pursuing on a research level,” said Dr. Claudine Isaacs, an oncologist at Georgetown University Hospital who works closely with carriers of BRCA1 and a related gene.

“This is work in a mouse,” she said. “It’s clearly too early to start recommending use of this agent.”

Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, the American Cancer Society’s deputy chief medical officer, said researchers and patients will “take interest in this topic and explore it further.”

He called the paper “elegant research,” but stressed that “it would not be appropriate in any way, shape or form that women start taking RU-486 for this purpose.”

The study appears in the Dec. 1 issue of Science.

Previous studies conducted by other researchers linked high progesterone levels with an increase in breast cancer risk, particularly in menopausal women who underwent hormone-replacement therapy that included progesterone and estrogen to ease symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats. That research, combined with the recent findings, lead scientists to believe that anti-progesterone could, in the future, provide women at risk for breast cancer with more prevention options.