A lot of research is yet needed before doctors can actually try spinal-tap tests in people who think they may have Alzheimer’s. But as of now, scientists are already preparing for larger studies to see if this potential “biomarker†of Alzheimer’s holds up.

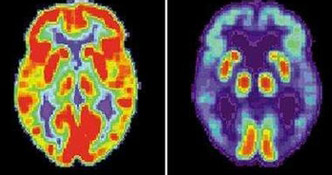

Currently, doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s mainly by symptoms. That makes early diagnosis particularly difficult, and even more advanced disease can be confused with other forms of dementia. Nor is there a good way to track the disease’s progression, important both for decisions about patient care as well as in testing the effectiveness of new drugs.

By hunting for one protein at a time, scientists have discovered a few other biomarker candidates in cerebrospinal fluid. But Relkin and colleagues at Cornell University expanded the hunt: Using a technology called proteomics, they simultaneously examined 2,000 proteins found in the spinal fluid of 34 people who died with autopsy-proven Alzheimer’s, comparing it to the spinal fluid of 34 non-demented people.

What emerged were 23 proteins, many that by themselves had never been linked to Alzheimer’s but that together formed a fingerprint of the disease.

Then the researchers looked for that protein pattern in the spinal fluid of 28 more people — some with symptoms of Alzheimer’s or other dementia, some healthy. The test indicated Alzheimer’s in nine of the 10 patients that doctors suspect have it, and incorrectly pointed out to three people.

“We’re looking to an era in which the kinds of uncertainties that many patients and their families face about the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease will no longer be a problem,” predicts Dr. Norman Relkin, a neurologist and the study’s senior researcher.

“A valid biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease is sorely needed,” said Dr. Sam Gandy, a neuroscientist at Philadelphia’s Thomas Jefferson University and spokesman for the Alzheimer’s Association.

That huge brain-scanning study is collecting spinal fluid samples from some participants, and Relkin has begun talks with those researchers about testing his results. At his own hospital, he’s using the protein test in a study of an experimental Alzheimer’s treatment to see if changes in the fingerprint may predict when the drug does or doesn’t work.

Scientists believe that Alzheimer’s begins its insidious brain attack years, even decades, before forgetfulness appears — and if so, there should be evidence of those changes in the spinal fluid, Relkin explained.