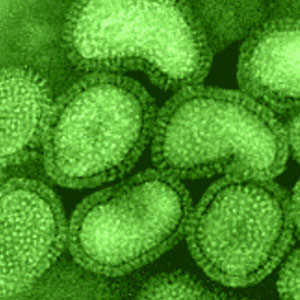

Influenza A is the same bug that most commonly makes people sick and is the reason behind several serious flu epidemics.

Mei Hong, Iowa State’s professor in Chemistry together with Sarah Cady, a graduate student in chemistry made these findings while studying the effects of amantadine, an antiviral drug on influenza.

The findings are very important since mutations of the type A virus have become resistant to amantadine treatment.

“In the last few years, amantadine resistance has skyrocketed among influenza A viruses in Asia and North America, making it imperative to develop alternative antiviral drugs,” said Hong and Cade in their paper.

According to Hong, making alternative antiviral drugs may become easier with the understanding of exactly how amantadine stops the flu virus.

During the research, the researchers studied the proton channel of a protein called M2, which a virus uses for its spread in healthy cells.

Hong and Cady used solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy-a technique similar to the magnetic resonance imaging technology that takes pictures of soft tissues in the body-for the purpose. The technology enabled them to discover and describe the motion and structure of the M2 proton channel in virus cells.

While studying the channel when cells were treated with amantadine and when they were not, the researchers made three findings.

First, the M2 protein is in constant motion, changing among various conformations, and amantadine treatment changes the rate of motion and reduces the number of possible conformations the protein can adopt. Secondly, the structure of the protein changes most prominently at two places facing the channel interior when cells are treated with amantadine. Finally, the tilt and orientation of the protein’s helices are subtly changed by amantadine.

The researchers say that the three events observed by them are necessary to block the ability of a virus to infect a healthy cell.

“We didn’t know that before. And now that makes it very clear what we should study next,” Hong said.

They are now planning to examine how mutant versions of the virus are able to resist the flu-stopping changes caused by amantadine.