Though the study still aroused skepticism over genetically modified babies, the scientists say that the embryos were still a product of a single male and single female.

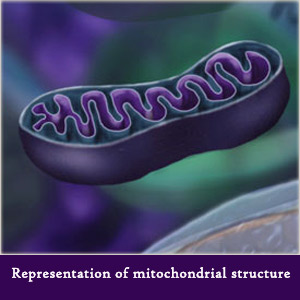

Diving into the theoretic part of it, the samples considered were of two females; one with a irregular mitochondrial structure and the other with a normal one. The genes replaced were that of the mitochondria which is the cell’s energy storehouse and is contained outside the nucleus of the female egg. The scientists created an embryo with the male and the female egg containing defective mitochondria.

They then transplanted the formed embryo into and emptied egg donated by the second female with the healthy mitochondria. So far 10 such embryos were created, none of which were allowed to develop for more that 5 days.

This study was undertaken to attempt correcting mistakes in the mitochondrial genetic code. These mistakes are believed to result in serious disorders including muscular dystrophy, epilepsy, strokes and mental retardation.

Patrick Chinnery, Professor of neurogenetics at the Newcastle University and part of the research team said “We are not trying to alter genes, we’re just trying to swap a small proportion of the bad ones for some good ones,”

He added “Most of the genes that make you who you are inside the nucleus and we’re not going anywhere near that.” The experts say only trace amounts of a person’s genes come from the mitochondria, and said it would be incorrect to say that the embryos have three parents.

The research funded by the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign, a British charity aims to create healthy embryos for couples to avoid passing on genes carrying diseases.

Scientists hope that after further experiments in the next few years the process might be available to parents undergoing in-vitro fertilization.

“If successful, this research could give families who might otherwise have a bleak future a chance to avoid some very grave diseases,” said Francoise Shenfield, fertility expert with the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. Shenfield said that further tests to determine the safety and efficacy of the process were necessary before it could be offered as a potential treatment. Shenfield was not part of the Newcastle University research.

In Japan, similar experiments were conducted using mice and led to the birth of healthy mice with corrected mitochondria genes.

The research was presented at a scientific conference recently, but has not been published in a scientific journal.