The empirical evidence is combined with a mathematical model. It was supposedly developed in cooperation with Prof. Lewi Stone of the department’s Biomathematics Unit. The experts were of the opinion that the bodies of men and women may have become reproductive opponents and not reproductive partners.

Dr Hasson commented, “The rate of human infertility is higher than we should expect it to be. By now, evolution should have improved our reproductive success rate. Something else is going on.â€

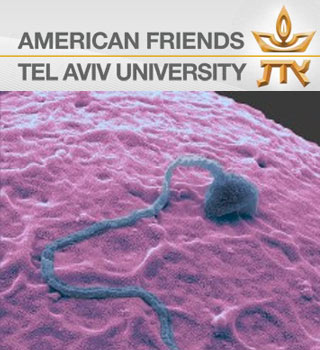

Over several years of evolution, womens’ bodies have apparently forced the sperm to become more aggressive, thereby gratifying the ‘super-sperm’ which is the strongest and fastest swimmer, by allowing it to penetrate the egg. In response, men could be over-producing these competitive sperms, by apparently producing many dozens of millions of them to add to their odds for successful fertilization. But the Law of Unintended Consequences may be demonstrated by these evolutionary strategies.

Dr Hasson mentioned, “It’s a delicate balance, and over time women’s and men’s bodies fine tune to each other. Sometimes, during the fine-tuning process, high rates of infertility can be seen. That’s probably the reason for the very high rates of unexplained infertility in the last decades.â€

The unintentional effects may have much to do with the timing. The first sperm to penetrate and combine with the egg apparently generates biochemical responses to obstruct other sperms from penetrating. This barrier may be required as a second penetrating sperm could destroy the egg. Nevertheless, in just the few minutes it takes for the obstruction to complete, today’s over-competitive sperm could be penetrating; thereby terminating the fertilization just after it’s started. Womens’ bodies too could have been developing resistance to this condition called as ‘polyspermy’.

Dr. Hasson remarked, “To avoid the fatal consequences of polyspermy, female reproductive tracts have evolved to become formidable barriers to sperm. They eject, dilute, divert and kill spermatozoa so that only about a single spermatozoon gets into the vicinity of a viable egg at the right time.â€

Any minute development in male sperm competence may be coordinated by a response in the female reproductive system.

Dr. Hasson commented, “This fuels the ‘arms race’ between the sexes and leads to the evolutionary cycle going on right now in the entire animal world.â€

Sperm could have also become more perceptive to environmental stressors such as anxious lifestyles or polluted environments.

Dr Hasson mentioned, “Armed only with short-sighted natural selection, nature could not have foreseen those stressors. This is the pattern of any arms race. A greater investment in weapons and defenses entails greater risks and a more fragile equilibrium.â€

Dr. Hasson remarked that IVF specialists may optimize fertility chances by calculating more cautiously, the amount of sperms located near the female ova. Sometimes nature also helps. Sexually adventurous women such as females of many birds and mammals who raise their children monogamously but like to take on other sexual partners, may assist in forming a more fertile future. But according to Hasson and Stone’s mathematical model, this is not always possible. Particular kinds of infertile sperm compete to the egg as any healthy sperm, and may obstruct the sperm of a fertile lover.

But Dr. Hasson will not recommend cheating, no matter what the source of infertility is. He advises infertile couples to frankly converse about all their options, and look for counseling if required.

This study was published in the journal Biological Reviews.