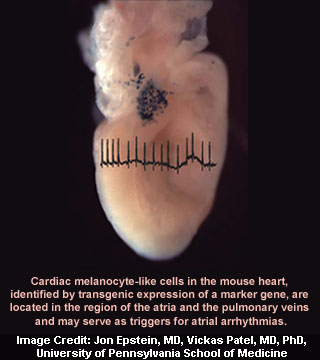

This group of cells is known to express the protein DCT, which is also involved in making the skin pigment melanin and in the detoxification of free radicals. The study authors also showed that the DCT-expressing cells in the mouse heart were noted to be a distinct cell type from heart-muscle cells and pigment-producing cells. However, they may perhaps carry out electrical currents vital for coordinated contraction of the heart.

Supposedly, the location of these cells in the pulmonary veins put forward their potential role in AF because AF can occur in these blood vessels. Moreover, atrial fibrillation seems to be a very common and devastating disease that seriously affects quality of life. Knowing the location of these cells could possibly assist in developing better treatments for AF.

“We already target the pulmonary veins for radiofrequency ablation, a nonsurgical procedure using radiofrequency energy similar to microwaves, to treat some types of rapid heart beating as a relatively new treatment, and sometimes cure, for AF,†explains Jonathan Epstein, MD, William Wikoff Smith Professor, and Chair, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology.

“For the most part, current drug therapy for atrial fibrillation has been disappointingly ineffective and drug therapy is often associated with burdensome side-effects,†says Vickas Patel, MD, PhD, and Assistant Professor of Medicine.

If these cells are truly the source of AF in some patients, and the authors may be able to figure out a way to identify them, then their ablation can be far more precise and targeted. Thus limiting possible side effects and making the procedure potentially more simple and rapid, and hence more cost effective.

However the authors caution more study appears to be required in order to get to the point where these ideas can be confirmed in patients. The findings seem to hold out promise for a more precise cellular target for treating this common disorder.

The findings of the study have been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.