This breakthrough is claimed to be such a vital part of immunology that UAB experts, in collaboration with Japanese researchers, are requesting that the gene connected to this antibody receptor be renamed to depict its function in early immune responses in a better way.

Fc mu receptor (FCMR) is said to be the suggested name for the gene. The name apparently defines a chief area of an immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody that supposedly fastens this receptor. IgM is believed to be the biggest antibody in the circulatory system. It is also alleged to be the first antibody on the scene in response to an attacking pathogen like a virus or bacteria. The IgM-tagged pathogens then apparently activate several immune responses through this receptor FCMR.

Formerly, scientists who had recognized this gene were of the opinion that they were dealing with a molecule that supposedly controlled cell death and they called it ‘toso’ which is said to be an indication to the Japanese medicinal sake frequently drunk on New Year’s Day to signify a long life. But the toso name seems incorrect, as were several of the former descriptions of this gene’s role. This was mentioned by Hiromi Kubagawa, M.D., a professor in the UAB Department of Pathology and the lead study author.

Kubagawa commented, “The new study shows, and DNA analysis helped us to confirm, that the Fc mu receptor is made from the gene we describe. This is a fundamental discovery that science has been waiting to answer for nearly 30 years.â€

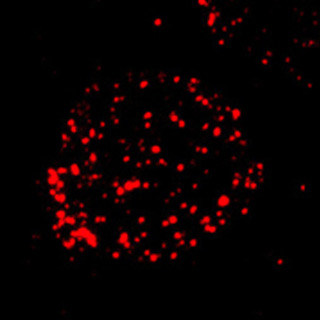

To recognize the true FCMR gene, the UAB experts applied chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells as a foundation of this gene, because such leukemia cells are apparently identified to over-express the Fc mu receptor. This supposedly facilitated experts to spot the FCMR gene more effectively.

The possible novel agents that aim and adjust FCMR role apparently hold promise in combating cancer, AIDS and autoimmune disorders. The genetic portrayal and appeal for renaming the gene apparently does not establish a direct function in any specific disease.

The study was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.