Cleft palate is apparently one of the most general congenital birth defects in humans. The present surgical treatment for the craniofacial abnormality is alleged to be frequently difficult and persistent, occasionally extending over several years before the treatment is said to be over.

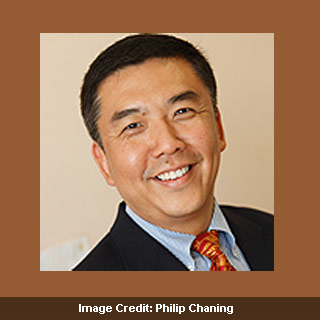

Yang Chai, the study’s principal investigator and director of the School of Dentistry’s Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, mentioned that cleft palate could cause grave impediments, counting trouble in eating and learning to speak. Nonetheless, close controlling of significant signaling molecules during palate configuration could someday enable doctors to undo a cleft palate sooner than the birth of the baby.

For instance, the protein Shh ought to stay inside a particular level in a growing fetus in order for a correct palate to develop. If too small or excess protein is expressed, a cleft palate could arise.

Two genes are claimed to be accountable for the controlling of Shh levels. Signaling from the Msx1 gene apparently fuels Shh production, while Dlx5 dampens Shh, thereby forming a strong equilibrium. Both genes are alleged to be important for the healthy growth of the palate, teeth and other skull and facial structures.

The fetal mice were said to be intentionally bred to have a fault in the Msx1 gene, thereby ensuing in need of expression of the Shh protein and the development of cleft palates. Nonetheless, when the effect of the Dlx5 gene was apparently curbed, additional Shh was effectively expressed and the palate started to regrow.

The palates were undamaged, when the mice were born. While a few of the oral structures apparently had slight dissimilarities as opposed to the palates in entirely healthy mice, the role of the saved palates was healthy, thereby enabling the newborn mice to feed naturally.

Yang Chai mentioned that with additional research into the genetic procedures behind cleft palate in humans, this ground-breaking finding could one day create a huge difference in how one averts or treats cleft palate in humans.

The research was published in the journal Development.