The new findings describe how host cells continue to survive despite being exploited by the parasite with the help of these protective mechanisms. The investigators used a multi-faceted approach to examine the parasite that is known to cause Chagas’ disease. They put to use bioinformatics, immunochemistry, intracellular colocalization microscopy along with in vitro enzymatic techniques that helped analyse the survival of T. cruzi in the host.

“We asked ourselves, ‘How is it possible that the host cells stay alive for so long with thousands of T. cruzi parasites consuming the host cell’s vital resources?’ We discovered that PDNF on the surface of the T. cruzi parasite essentially inhibits cell death signals and activates cell-protective mechanisms, ensuring T. cruzi sufficient time to develop and reproduce in the host cell,” mentions senior author Mercio Perrin, MD, PhD, professor in the pathology department at Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and member of the immunology program faculty at the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts.

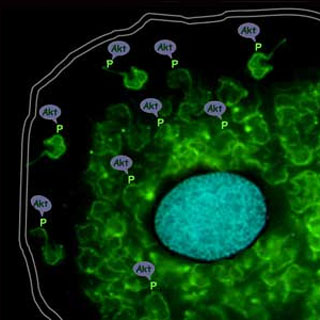

Apparently PDNF was found to be a substrate and activator of Akt kinase which is an enzyme that seems to promote cell survival by inhibiting ‘cell death’ proteins. This was put forth by Perrin and co-author Marina Chuenkova, PhD, a research instructor in the pathology department at TUSM and the Sackler School.

“Further investigation showed that within T. cruzi-infected cells, PDNF also activates increased production of Akt, prolonging its protective effects,” remarked Chuenkova. “Akt is a key regulator of diverse cellular processes, and supports cell survival not only by inhibiting apoptotic molecules, but additionally by increasing nutrient uptake and metabolism,”

“In short, the T. cruzi parasite has a means of establishing life insurance once it has invaded the host. If we can fully understand the mechanisms behind this protection, we can begin to explore ways to undermine it with treatment,” added Perrin.

Typically transmitted to humans via blood-feeding insects, Chagas’ disease supposedly infects an estimated 8 to 11 million people throughout Mexico, and Central and South America. Even though it is considered to be rare in the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shares that nearly 300,000 people with Chagas’ disease live in the U.S.

Fever or swelling at the site of the insect bite could be the acute phase of Chagas’ disease. Many people however may not experience symptoms at all and if left untreated, the disease could enter an indeterminate phase with no symptoms. Individuals appear to be unaware of their infection during this phase. But approximately 30 percent could eventually develop life-threatening complications of the disease like enlargement of the digestive tract and/or heart.

This finding has been published in the online issue of Science Signaling.