A novel research by experts from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute appears to proffer a new agent for some types of drug-resistant, non-small cell lung cancers. The team claim to have uncovered a compound capable of halting a common type of drug-resistant lung cancer. This seemingly was thanks to the ability to make, test, and map the atomic structure of new anti-cancer agents.

According to the researchers, they were able to thwart non-small cell lung cancers that seemed to have become invulnerable to the drugs Iressa and Tarceva by the novel compound formulated in a Dana-Farber lab.

Claiming to have a basic chemical framework different from that of other cancer drugs, the compound was found to act against a protein called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase. It is known to carry a specific structural defect.

“This type of drug discovery, in which an agent is developed for a specific gene or protein target, and then screened against cancer cells as well as in laboratory models, is rare in academic medicine,” says the senior author Pasi A. Janne, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH).

The researcher further explains, “This requires contributions from researchers in multiple disciplines and a coordinated approach to planning experiments and sharing results. That we accomplished this is evidence of the contribution academic medical centers can make to the quest for new cancer treatments.”

This new finding demonstrates how quickly lung cancer research and treatment is apparently advancing. The Dana-Farber investigators speculate that present agents seem to lose their potency due to their inability to bind as tightly or fully to the EGFR T790M protein as they typically should.

Led by chemical biologist Nathanael Gray, PhD, the researchers claim to now have enhanced the fit with the help of a group of inhibitors that included a different structural scaffold dubbed a pyrimidine core. This, the experts were of the opinion would probably mesh more thoroughly. Next, the agent was lab-tested by them in NSCLC cells with EGFR T90M. They discovered many that appeared to be up to 100 times more potent than quinazolines in restricting cell growth.

In addition this, the researchers surprisingly also found these compounds to be approximately 100 times less powerful at slowing the growth of cells with normal EGFR. This seems to suggest that they would be less likely to produce side effects as compared to current drugs. The agent pyrimidine WZ4002 was found to have performed the best.

“This work provides a possible therapeutic chapter to a longstanding record of validating EGFR as a drug target,” shares Gray. “This has involved the identification of activating mutations in EGFR as a predictor of drug response, the discovery of multiple drug resistance mechanisms, and the elucidation of how these mutations work at an atomic level.”

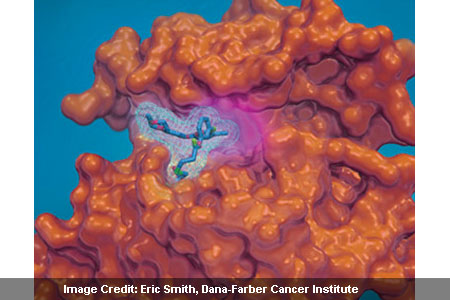

As part of follow-up experiments, the pyrimidine agents were screened in mice with Iressa- and Tarceva-resistant NSCLC tumors driven by EGFR T790M. Conducted by Dana-Farber and BWH’s Kwok-Kin Wong, MD, PhD crystallography analysis was conducted to ascertain the molecular structure of the pyrimidines. This was done to offer a better picture of why they were so potent and how they target EGFR T790M cells so accurately.

“Not only did we determine that the compound WZ4002 could slow tumor growth, we also demonstrated that it is possible to selectively target the drug-resistant mutant EGFR in tumors, with relatively less effect on the normal EGFR in healthy tissues,” mentions Wong.

The researchers suggest that additional work is needed to determine whether WZ4002 and its chemical cousins would be effective therapies. However they caution that the discovery could demonstrate the power of screening specially designed compounds against cancers with certain genetic quirks.

The finding is to be published in the December 24/31 issue of the journal Nature.