In order to gauge stress levels on a daily basis, Bert Arnrich, Cornelia Setz, Gerhard Tröster and their team of experts at ETH Zurich’s Electronics Laboratory have supposedly formulated an electronic stress assistant.

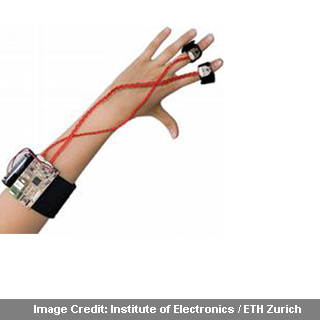

The scientists utilized diverse pointers to find out stress levels, counting the skin conductance on the fingers, the heart and breathing rates, and the quantity of the stress hormone cortisol in saliva. Moreover, they gauged leg, foot and arm movements and enclosed a chair with pressure sensors to document how frequently an individual alters his or her posture while seated.

To check the precision of their measurement system, the ETH-Zurich scientists performed a comprehensive study in partnership with psychologists Roberto La Marca and Ulrike Ehlert from the Psychological Institute of the University of Zurich. Approximately more than 30 subjects were requested to participate in their stress study which was camouflaged as an easy mental arithmetic test. Actually, nevertheless, they had to crack particular mathematical problems on a computer under time and social pressure.

If the participant was good at cracking mathematical tasks, the program mechanically chose more hard tasks. Consequently none of the subjects could answer more than half of the tasks, even if they were proficient in mathematics. Furthermore, volunteers were continuously shown that their performances were seemingly below average as opposed to a ‘standard group’. Lastly, the examiner placed the subjects under extra pressure by providing them insensitive feedback on their performances.

The outcomes of the study appeared to expose that the stress assistant worked well. It was seen that in around 83 percent of the cases, the system could identify stress levels properly based on skin conductance. This is owing to the fact that the body seems to exude more sweat when under stress, particularly on the palms and soles of the feet. So the conductance of the skin apparently augmented.

The pressure sensors on the chair also supposedly offered helpful information for stress recognition and enabled to distinguish stress consistently in roughly 73 percent of the cases. Even though a few subjects froze, majority of the subjects seemed to move back and forth more frequently on the chair while under stress.

Study authors could make assertions about a person’s stress level after merging techniques and not including other factors that apparently cause sweating like physical exertion.

Professor Gerhard Tröster’s senior assistant is now supposedly crafting electronic stress recognition more within two new EU-funded projects. The study authors would also want to determine whether their techniques may be used on patients who experience manic depressive disorders. They are apparently keen to investigate find out whether manic and depressive conditions could be gauged and how acute they are.

Arnrich’s team are said to be coming up with more comfortable sensors. Some alternatives comprise of gauging skin conductance on feet as the inner side of the feet apparently respond similarly to the palm of the hand, i.e. with augmented perspiration. Suitable sensors may be incorporated into normal socks. Consequently it could soon be feasible for people and doctors to access details on every day stress levels around the clock and avert stress-related illnesses.