Cells seemed to have diverse defense programs to protect themselves from getting out of control under stress and from splitting without stopping and contracting cancer. So far, scientists seemed to have assumed that these defensive systems were said to be encouraged separately from each other.

Now for the first time, by means of an animal model for lymphoma, cancer experts of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC) Berlin-Buch and the Charité – University Hospital Berlin in Germany have apparently illustrated that these two protection programs function together via an interaction with standard immune cells to avert tumors. The discoveries of Dr. Maurice Reimann and his colleagues in the study group headed by Professor Clemens Schmitt may be of basic significance in the battle against cancer.

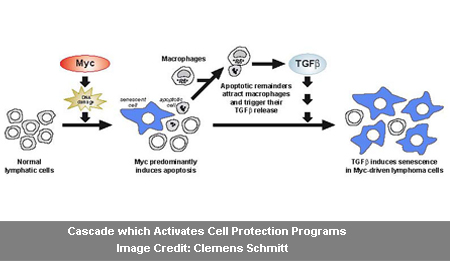

Scientists have apparently known for quite a long time that oncogenes themselves may activate these cell protection programs in an early developmental stage of the disease. This may clarify why a few tumors take decades to contract until the occurrence of the disease. The Myc oncogene triggers apoptosis, supposedly provoke impaired cells to commit suicide so as to defend the organism as a whole. Via chemotherapy, physicians seemed to set off this protection program to treat cancer.

The second protection program is believed to be senescence. This program is apparently activated by another oncogene, the ras gene. Senescence halts the cell cycle, and the cell may no longer split. The cell apparently carries on living and is still metabolically active. Professor Schmitt, physician at Charité University Hospital and research group leader at the MDC could demonstrate on an animal model for lymphoma that senescence may obstruct the growth of early-stage malignant tumors.

Now, for the first time, Dr. Reimann, Dr. Soyoung Lee, Dr. Christoph Loddenkemper, Dr. Jan R. Dörr, Dr. Vedrana Tabor and Professor Schmitt have offered proof that the Myc oncogene seems to play a vital function in the generation of both protection programs devoid of the attendance of the ras oncogene.

Professor Schmitt commented, “What is remarkable about this finding is that an oncogene can first trigger apoptosis and interact with the tumor stroma – the tissue that surrounds the tumor which also contains healthy cells – and with the immune system and then is able to switch on signals which lead to tumor senescence.â€

The Myc oncogene apparently triggers in the lymphoma cells. The dying, apoptotic cells seemingly attract macrophages of the immune system, which appears to consume and dispose of the dead lymphoma cells. The activated macrophages in turn supposedly discharge messenger molecules, counting the cytokine TGF-beta. It could obstruct the development of cancer cells in the early stage of a tumor disease.

Professor Schmitt remarked, “Our findings promise to have fundamental significance for elucidating the pathogenesis not only of lymphoma cancers, but of cancer in general. Our results indicate that senescence triggered by the immune system’s messenger molecules may be a further important active principle, apart from apoptosis induced by chemotherapy.

The expert added that if by inducing senescence they could obtain a sustained suppression of the cancer cells they can no longer destroy, this would mean exciting new possibilities for therapy.

Presently, the study authors in Professor Schmitt’s group are said to be concentrating intensively on chemotherapy-mediated senescence.