But steroids appeared to encompass substantial side effects, don’t constantly work, and their system of action in hemangioma has supposedly stayed unknown. Scientists at Children’s Hospital Boston lately found out that infantile hemangiomas appear to be derived from stem cells, and have apparently used these stem cells to comprehend this tumor in the laboratory in a better way.

Around 4 – 10 percent of infants supposedly suffer from hemangiomas. They are said to be noncancerous tumors involving a knotted mass of blood vessels. Formerly, it was hypothesized that steroids perform on endothelial cells, which supposedly make up around 30 percent of cells in the tumor.

The new study headed by dermatologist Shoshana Greenberger, MD, PhD, working in the lab of Joyce Bischoff, PhD, in Children’s Vascular Biology Program, exhibits that steroids seemingly impede with a much unusual and more ancient cell type, hemangioma stem cells.

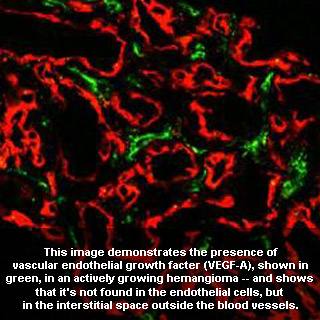

Greenberger and Bischoff additionally displayed that steroids function by holding back hemangioma stem cells’ capability to fuel blood vessel development, and that they do so by closing down generation of a certain issue known as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A). VEGF is believed to be well known as a stimulator of angiogenesis in cancer and age-related macular degeneration.

Steroids generally lead to only stabilization of hemangioma development, and around 30 percent of hemangiomas don’t react to steroid treatment. Steroids also appeared to encompass side effects counting facial swelling, hyperactivity, growth retardation and augmented blood pressure. Even though the consequences on the look may appear minor, study signifies that a baby’s physical appearance could hinder with maternal bonding.

Greenberger, Bischoff and colleagues worked with hemangioma stem cells isolated from patient tissue samples supplied by Mulliken and illustrated that when human hemangioma stem cells were apparently pretreated with dexamethasone, then appeared to be entrenched in mice, the tumors that formed supposedly encompassed far lesser blood vessels. Dexamethasone seemingly repressed the stem cells’ generation of VEGF-A, but did not curb VEGF-A generation by endothelial cells from the same hemangioma. When VEGF-A production was held back in hemangioma stem cells by means of shRNA silencing, then fixed in the mice, there seemed to be an 89 percent decrease in vessel development. VEGF-A was supposedly identified in vigorously developing hemangiomas, but not in degenerating hemangiomas

Preceding study in Bischoff’s lab and that of Bjorn Olsen, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, seems to signify that hemangiomas may result from an in utero mutation in a stem cell intended to turn into an endothelial cell, thereby causing a disturbance in the usually well-ordered procedure of blood vessel development.

Under a 2008 Translational Research Program grant from Children’s, Bischoff’s lab has apparently been applying hemangioma stem cells to asses a record of present medications that might particularly hold back the proliferation of the hemangioma stem cells, and thus restrict development of the hemangioma tumor.

The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.