The study investigated the efficiency of a class of robotic devices crafted at MIT. It appears to signify that in chronic stroke survivors, robot-assisted therapy apparently resulted in reasonable developments in upper-body motor function and standard of life six months post the conclusion of active therapy. These improvements were said to be considerable when pitted against a group of stroke patients who were given the conventional treatment.

Furthermore, the robotic therapy which presumably includes a more powerful routine of activity as opposed to traditional stroke therapy did not augment the total healthcare costs per stroke patient. It could also make intensive therapy accessible to more patients.

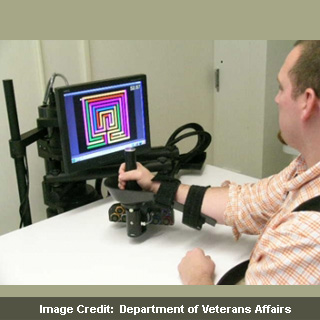

Hermano Igo Krebs, a principal research scientist in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, began building the robotic system, dubbed MIT-Manus, over 20 years ago. The system is supposedly based on the code that stroke patients gain the most when they have to make a conscious attempt during physical therapy. The patients have to clutch a robotic joystick that steers the patient’s arm, wrist or hand as he or she strives to make particular movements, thereby aiding the brain to come up new connections that could finally assist the patient re-learn to move the limb on his or her own.

Study authors at four VA hospitals in Baltimore, Seattle, West Haven, Conn., and Gainesville, Fla supposedly pitted the MIT-Manus system against a high-intensity rehab program provided by a human therapist, which was planned particularly for this study. Every group comprised of roughly 50 patients, who were also weighed against a group of 28 stroke patients who were given supposed ‘usual care’ i.e. general health care and three hours per week of conventional physical therapy for their stroke-damaged limb.

Patients using the MIT-Manus system clutch a joystick-like handle connected to a computer monitor that seems to exhibit jobs just like those seen in easy video games. In a usual task, the subject tries to shift the robot handle toward a moving or immobile target displayed on the computer monitor. If the individual begins moving in the wrong direction or does not move, the robotic arm slightly pushes his or her arm in the correct direction.

Patients in the study were given therapy three times a week for 12 weeks, and during every hour-long session, they apparently made several recurring motions with their arms. After 12 weeks, tests seemingly divulged a small but statistically considerable augment in standard of life and a reasonable development in arm function. When the participants were examined again at 36 weeks, both the robot therapy group and intensive human-assisted therapy group apparently exhibited progress in arm movement and strength, daily function and quality of life as opposed to the usual care group.

The high-intensity interactive physical therapy provided to patients who were not given robot-assisted therapy was said to be crafted particularly for comparison reasons for this study and is not normally obtainable. Krebs thinks that once the robotic devices can be mass-produced, which he anticipates to happen in the subsequent 10 years, the expenses may decline enough that their use could become extensive.

The study was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.