Presently there is no cure for herpes viruses. When an individual is affected by an infection, the virus remains in the body for a lifetime and appears inactive for a long time. When the virus turns active it can cause a number of problems particularly cold sores, blindness, encephalitis, or cancers.

Senior author Ekaterina Heldwein, PhD, assistant professor in the molecular biology and microbiology department at Tufts University School of Medicine shares, “Most viruses need cell-entry proteins called fusogens in order to invade cells. We have known that the herpes virus fusogen does not act alone and that a complex of two other viral cell-entry proteins is always required. We expected that this complex was also a fusogen, but after determining the structure of this key protein complex, we found that it does not resemble other known fusogensâ€.

He further quotes, “This unexpected result leads us to believe that this protein complex is not a fusogen itself but that it regulates the fusogen. We also found that certain antibodies interfere with the ability of this protein complex to bind to the fusogen, evidence that antiviral drugs that target this interaction could prevent viral infection.

Most Americans are affected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). This mainly causes cold sores among most of these individuals by the time they reach their 20s. HSV-2 that is known for genital herpes affects nearly one among every six Americans.

Jeremy M. Berg, PhD, director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) at the National Institutes of Health reveals, “Katya Heldwein’s work has resulted in a map of the protein complex needed to trigger herpes virus infection. The NIH Director’s New Innovator Awards are designed to support such breakthroughs. This research not only adds to what we know about how herpes viruses infect mammalian cells, but also sets the stage for new therapeutics that restrict herpes virus’s access to the cellâ€.

HSV-2 is a sexually-transmitted disease and is known to carry along many complications. They mainly include persistent painful genital sores and psychological distress. However if it is transferred from a mother to child the newborn infant may face fatal infections.

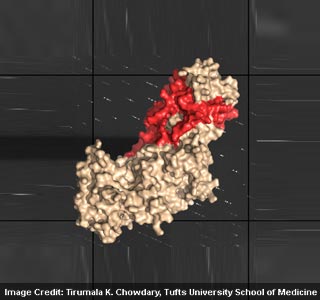

First author Tirumala K. Chowdary, PhD, a postdoctoral associate in the department of molecular biology and microbiology at TUSM and member of Heldwein’s lab elucidates, “We hope that determining the structure of this essential piece of the herpes virus cell-entry machinery will help us answer some of the many questions about how herpes virus initiates infection. Knowing the structures of cell-entry proteins will help us find the best strategy for interfering with this pervasive family of virusesâ€.

Experts used x-ray crystallography with cell microscopy methods to examine the structure and utility of this cell-entry protein complex in HSV-2. They are presently developing a molecular movie that explains how herpes virus enters the cell.

These findings were published online in advance of print in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.